Teacher: “What are your greatest dreams about your future?”

Jeremy: “I want to have my own house with roommates, good friends,

a fun job and be learning.”

Teacher: “What are your greatest fears about your future?”

Jeremy: “That I will not have enough money.”

Teacher: “What barriers might get in the way of accomplishing your goals?”

Jeremy: “You know I need good helpers. I need people that respect my intelligence.”

-Interview with Jeremy Sicile-Kira

Transition Year 2007-08

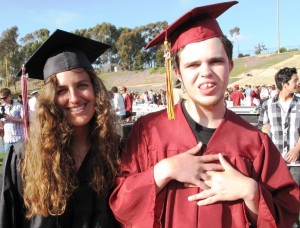

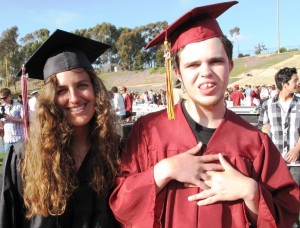

With two teenagers who will soon be out of school, there has been much reflection and soul searching taking place in my home lately as to whether or not we’ve made the right decisions as parents over the years. Rebecca, our neurotypical teenager, has just started driving and is becoming more independent. In hindsight, there is not much I would do differently if we had to start raising her all over again.

My thoughts concerning Jeremy, our 19-year-old son with autism, are somewhat different. Those who have seen him on the MTV True Life segment “I Have Autism” will remember his can-do spirit and his determination to connect with other people, but also how challenged he is by his autism. Obviously, there are many more options available to help people like Jeremy today than when he was a baby. Over the last few years, as we considered how to best prepare Jeremy for the adult life he envisioned, I wondered what we could have or should have done differently when he was younger.

This led me to think: What would today’s adults on the autism spectrum point to as the most important factors in their lives while they were growing up? What has made the most impact on their lives as adults in terms of how they were treated and what they were taught as children? What advice did they have to offer on how we could help the children of today? I decided to find out. I interviewed a wide-range of people—some considered by neurotypical standards as “less able,” “more able” and in-between; some who had been diagnosed as children; and some diagnosed as adults.

The result of these conversations and e-mails became the basis of my latest book, Autism Life Skills: From Communication and Safety to Self-Esteem and More—10 Essential Abilities Your Child Needs and Deserves to Learn (Penguin, October 2008). Although some areas discussed seemed obvious on the surface, many conversations gave me the “why” as to the challenges they faced, which led to discussions about what was and was not helpful to them. No matter the differences in their perceived ability levels, the following 10 skill areas were important to all.

Sensory Processing

Making sense of the world is what most adults conveyed to me as the most frustrating area they struggled with as children, and that impacted every aspect of their lives: relationships, communication, self-awareness, safety and so on. Babies and toddlers learn about the world around them through their senses. If these are not working properly and are not in synch, they acquire a distorted view of the world around them and also of themselves.

Most parents and educators are familiar with how auditory and visual processing challenges can impede learning in the classroom. Yet, for many, sensory processing difficulties are a lot more complicated and far reaching. For example, Brian King, a licensed clinical social worker who has Asperger’s, explains that body and spatial awareness are difficult for him because the part of his brain that determines where his body is in space (propioception) does not communicate with his vision. This means that when he walks he has to look at the ground because otherwise he would lose his sense of balance.

Donna Williams, Ph.D., bestselling author and self-described “Artie Autie,” had extreme sensory processing challenges as a child and still has some, but to a lesser degree. Donna talks about feeling a sensation in her stomach area, but not knowing if it means her stomach hurts because she is hungry or if her bladder is full. Other adults mention that they share the same problem, especially when experiencing sensory overload in crowded, noisy areas. Setting their cell phones to ring every two hours to prompt them to use the restroom helps them to avoid embarrassing situations.

Many adults found it difficult to tolerate social situations. Some adults discussed how meeting a new person could be overwhelming—a different voice, a different smell and a different visual stimulus—meaning that difficulties with social relationships were not due simply to communication, but encompassed the total sensory processing experience. This could explain why a student can learn effectively or communicate with a familiar teacher or paraprofessional, but not a new one.

The most helpful strategy was knowing in advance where they were going, who they were going to see and what was going to happen, so that they could anticipate and prepare themselves for the sensory aspects of their day. Other strategies included changing their diet, wearing special lenses, having a sensory diet (activities done on a regular basis to keep from experiencing sensory overload), undergoing auditory and vision therapy, as well as desensitization techniques.

Communication

The ability to communicate was the second most important area of need cited by adults. All people need a form of communication to express their needs, in order to have them met. If a child does not have an appropriate communication system, he or she will learn to communicate through behavior (screaming or throwing a tantrum in order to express pain or frustration), which may not be appropriate, but can be effective. Sue Rubin, writer and star of the documentary “Autism is a World,” is a non-verbal autistic college student and disability advocate. She often speaks about the impact of communication on behavior. She shares that as she learned to type she was able to explain to others what was causing her behaviors and to get help in those areas. In high school, typing allowed her to write her own social stories and develop her own behavior plans. As her communication skills increased, her inappropriate behaviors decreased.

Those with Asperger’s and others on the more functionally able end of the spectrum may have more subtle communication challenges, but these are just as important for surviving in a neurotypical world. Many tend to have trouble reading body language and understanding implied meanings and metaphors, which can lead to frustration and misunderstanding. Michael Crouch, the college postmaster at the Crown College of the Bible in Tennessee, credits girls with helping him develop good communication skills. Some of his areas of difficulty were speaking too fast or too low, stuttering and poor eye contact. When he was a teenager, five girls at his church encouraged him to join the choir and this experience helped him overcome some of his difficulties. Having a group of non-autistic peers who shared his interests and provided opportunities for modeling and practicing good communication skills helped Michael become the accomplished speaker he is today.

Safety

Many on the spectrum had strong feelings about the issue of safety. Many remember not having a notion of safety when little, and putting themselves in unsafe situations due to sensory processing challenges. These challenges prevented them from feeling when something was too hot or too cold, if an object was very sharp or from “seeing” that it was too far to jump from the top of a jungle gym to the ground below.

Many adults described feeling terrified during their student years, and shared the fervent hope that with all the resources and knowledge we now have today’s students would not suffer as they had. Practically all recounted instances of being bullied. Some said they had been sexually or physically abused, though some did not even realize it at the time. Others described how their teacher’s behaviors contributed directly or indirectly to being bullied. For example, Michael John Carley, Executive Director of GRASP and author of Asperger’s From the Inside Out, recalls how his teachers made jokes directed at him during class, which encouraged peer disrespect and led to verbal bullying outside the classroom.

A school environment that strictly enforced a no-tolerance bullying policy would have been extremely helpful, according to these adults. Sensitizing other students as to what autism is, teaching the child on the spectrum about abusive behavior, and providing him/her with a safe place and safe person to go to at school would have helped as well. Teaching them the “hidden curriculum,” so they could have understood what everyone else picked up by osmosis would have given them a greater understanding of the social world and made them less easy prey.

Self-Esteem

Confidence in one’s abilities is a necessary precursor to a happy adult life. It is clear that those who appear self-confident and have good self-esteem tend to have had a few things in common while growing up. The most important factor was parents or caretakers who were accepting of their child, yet expected them to reach their potential and sought out ways to help them. Kamran Nazeer, author of Send in the Idiots: Stories from the Other Side of Autism, explains that having a relationship with an adult who was more neutral and not as emotionally involved as a parent is important as well. Parents naturally display a sense of expectations, while a teacher, mentor or a therapist can be supportive of a child and accepting of his/her behavioral and social challenges. Relationships with non-autistic peers, as well as autistic peers who share the same challenges were also important to developing confidence.

Pursuing Interests

This is an area that many people on the spectrum are passionate about. For many, activities are purpose driven or interest driven, and the notion of doing something just because it feels good, passes the time of day or makes you happy is not an obvious one. Zosia Zaks, author of Life and Love: Positive Strategies for Autistic Adults, told me that, as a child, she had no idea that she was supposed to be “having fun”—that there were activities that people participated in just for fun. It was one of those things about neurotypical living that no one ever explained to her.

As students, some of these adults were discouraged from following their obsessive (positive translation: passionate) interest. Others were encouraged by parents and teachers who understood the value of using their interest to help them learn or develop a job skill. For example, when he was little, author and advocate Stephen Shore used to take apart and put together his timepieces. Years later, this interest was translated into paid work repairing bicycles at a bike store.

Self-Regulation

Respondents believed this is a necessary skill for taking part in community life. Many children on the spectrum suffer from sensory overload. It can also be difficult for them to understand what they are feeling and how to control their emotional response. Dena Gassner, MSW, who was diagnosed as an adult, believes it is necessary for children to be able to identify their “triggers” and that parents and educators should affirm to the child that whatever he or she is feeling is important. Even if it does not make sense to the adult, whatever the child is feeling is true for him or her. Various methods can be used to help them become more self-aware over time, to recognize when they are approaching sensory or emotional overload and to communicate the need for a break. As they get older, giving them more responsibility for scheduling their own breaks and choosing their own appropriate coping strategy can be very empowering.

Independence

Independence is an important goal, but may take longer than expected. Zosia Zaks told me that parents of children with autism need to realize and accept that they will be parenting for a lot longer than parents of neurotypical children. She has a point, but I never thought I’d still be discussing certain self-care issues when my son was old enough to vote. For many that I interviewed, some skill acquisition came later in life, and many are still improving themselves and their essential skills. This is nice to know because so often, as parents and educators, we hear about the “windows of opportunity” in terms of age and can become discouraged by our own inner cynics and other well-meaning doubters (“If they haven’t learned by now….”).

When discussing self-sufficiency, many stated that the two greatest challenges were executive functioning (being able to get and stay organized) and sensory processing. Doing chores and establishing routines helped some as children to learn organizational skills and responsibility—two essential foundations for self-sufficiency.

Social Relationships

Relationships are important to all human beings, but are difficult for many on the spectrum. The adults I communicated with make it clear they enjoy having relationships, including those who are mostly non-verbal, such as Sue Rubin and D.J. Savarese (who wrote the last chapter of Reasonable People). However, understanding the concept of different types of relationships and knowing the appropriate behaviors and conversations expected does not come naturally, and can be magnified for those who are non-verbal.

Many adults, such as Dena Gassner and Zosia Zaks, discussed the importance of teaching children interdependence skills—how to ask for help, how to approach a store clerk, how to network as they get older. For them, interdependence did not come as easily as it does for neurotypicals. Yet, asking people for assistance—what aisle the cookies are located in, the name of a plumber when your sink is stopped up, letting people know you are looking for a job or apartment—is how social and community life functions.

Self-Advocacy

Effective self-advocacy entails a certain amount of disclosure. All of the adults I spoke with believed that children should be told about their diagnosis in a positive manner. Michael John Carley, who was diagnosed following the diagnosis of his son, says he always felt different than others. Getting a diagnosis was liberating because then he knew why he felt different. On the topic of disclosure to others, some believe in full disclosure to all, while others choose to disclose only the area of difficulty.

Like many her age, Kassiane Alexandra Sibley, who wrote a chapter of the book Ask and Tell, was improperly diagnosed before discovering at age 18 that she had an autism spectrum disorder. She had to learn self-advocacy skills the hard way. Like many I spoke with, Kassiane believes that teaching children when they are young to speak up for themselves is the most important gift we can give them.

Earning a Living

This is an issue of major concern for many on the spectrum. Some of the adults I spoke with struggled for years before finding an area in which they could work. The life skills discussed earlier in this article impact tremendously on a person’s ability to find, get and keep a job. Many people on the spectrum continue to be unemployed or underemployed, which means we need to rethink our approach in how we are transitioning our youth from being students to being contributing members of society.

Temple Grandin, who co-authored the book Developing Talents, says that parents should help their children develop their natural talents and that young people need mentors to give them guidance and valuable experience. Authors John Elder Robinson (Look Me in the Eye) and Daniel Tammet (Born on a Blue Day) both credit their Asperger’s for giving them the talents on which they have based their successful businesses. For those whose talents are less obvious, a look at the community they live in and the service needs that exist there can be an option for creating an opportunity to earn money. My son Jeremy and his teacher created a sandwich-delivery business and a flower business on his high school campus as part of his work experience. Customized employment, including self-employment, is an option that, with careful planning and implementation, can be a solution for some.

In retrospect, there are different choices I could have made in raising and educating Jeremy these past 19 years. However, after conversations and e-mails with many different adults on the spectrum, I have concluded that there is one factor I would not have changed, the formula I used for providing a solid foundation for both of my children: Take equal parts love, acceptance and expectation, and mix well.

This first appeared in the Advocate Magazine in 2008, published by the National Autism Society of America